This story comes from the sidelines of the research for my novel-in-very-slow-progress. A friend lent me a book by Grigoriy Semyonovich Kan, published in St. Petersburg two years ago: Natalia Klimova. Her life and struggle [Кан, Г.С. Наталья Климова. Жизнь и борьба. С-Петербург, Издательство имени Н.И. Новикова, 2012]. I had but cursory familiarity with Klimova's name before I opened the book, and I read the volume 'with my mouth gaping,' as they say in Russian. Here's something between a brief summary and a review of this biography.

Klimova was born in Ryazan in 1885; her father, a lawyer, was an elected member of the representative council of small landowners (земское собрание)--Russian Empire's narrow concession to the idea of self-government. Her mother, Liubov Vyropaeva, came from the old Russian gentry and in 1870 became one of the first, if not the first, Russian woman to receive a medical degree--in Switzerland. She specialized in gynecology, established a respectable practice in Ryazan. She died in 1894, undergoing an operation for an ectopic pregnancy. A few years after her death, her husband and Natasha's father married Liubov's sister Olga, and so Natasha's aunt became her step-mother.

At first, Natasha tried to follow in her mother's footsteps. In 1903 she arrived to St. Petersburg and entered the women's higher education courses that would prepare her for the entrance exams to the Women's Medical Institute that by then existed in the capital. In 1904, Russia entered the war with Japan that seemed senseless to most young people, radicalizing many and leading to a renewed vigor in protests against the autocratic government--the protests that in 1905 erupted into general worker strikes and a large scale revolutionary movement, brutally broken up by Nicholas II's government and army. In December of that year, workers and students organized an armed protest in Moscow, and Klimova was among those who carried revolvers and ammunition to the barricade lines.

Klimova joined the Socialist Revolutionary party (illegal, as all socialist parties in Russia at that time), advocating for land reforms (transfer of land to the peasants) and self-government via a democratic election process. Her favorite reading at the time was Nietzsche and Tolstoy, a combination fairly typical to the disenfranchised young people of the rapidly industrializing Russia. According to Kan, from Tolstoy Klimova took the disgust with the existing class system, the wealthy "who feed on the poverty, debauchery, and suffering of millions."

Where Tolstoy rejected violence as the means of attaining social order, Nietzsche took over: "Humanity is what one must eclipse. . . . What matters in a human being is that he's a bridge, not the aim: one can only love the passage and the demise in a human being. . . . I love not those who look to the stars for the reasons to perish as victims, but those who actively bring the sacrifice of themselves to the earth, so that one day the earth can be the earth of the new man." [I'm translating this stuff from the Russian, trying to capture the style of the old-fashioned Russian translations of Nietzsche.]

So, Tolstoy and Nietzsche: an explosive combination of asceticism, ideas of equality and classless

society, Pyotr Stolypin. Stolypin, Prime Minister of Nicholas II's government, today is often remembered as a reformer; in 1907 he was responsible for suppressing the revolution and for increasing the punishments for the revolutionaries. (His slogan, "Levelheadedness comes first, reforms second [Сначала успокоение, потом реформы]".) Carrying bombs, the terrorists entered Stolypin's dacha. Things didn't go as planned--Stolypin's security became alarmed, and the terrorists exploded the bombs too early. Twenty four (including the terrorists) died instantly, and sixty more were hurt; Stolypin himself was unharmed. Klimova was not on the premises during this action, but she'd been instrumental in transporting and storing the bombs. The vast the surviving members of the terrorist organization, including Klimova, were arrested and tried. Stolypin didn't survive for very long: he died in 1911, in Kiev, at the hand of another terrorist.

with the hero worship and the challenge to stretch personal and social limits to achieve her goals. In 1906, Klimova joined a terrorist group who aimed to kill

Klimova was sentenced to death by hanging. A short while later, the sentence was commuted to imprisonment for life. While expecting her execution, she wrote a letter to her family that somehow made its way into print in a St. Petersburg journal. This letter, along with the other of her personal documents that survived the 20th C, is reprinted in the back of Kan's book. A unique and fascinating document, it's fairly abstract, perhaps too abstract to our contemporary tastes: she talks of fear of death, of what she believes might happen after her death: "I don't believe in any 'future lives.' . . . If the matter that my body's made of chooses to become the green grass of 1907, and its energy--the electricity that shines over Stolypin's cabinet, what have I to do with that?" She talks of life, of experiencing the heightened state of awareness on the brink of her death: "The dominant feeling is that of a special kind of inner freedom. It's--it's terribly difficult to explain. . . . In it, there's the pride of a person who has faced death and calmly and simply told her, 'I'm not afraid of you.'" Tolstoyan thought (Kan shows to what extent her thoughts on death were inspired by Tolstoy) acquires a whole new meaning under the pen of a twenty-one year old girl.

In another document, a memoir of being imprisoned in the famed Peter and Paul Fortress, Klimova writes: "I can't shake a very odd sensation. . . . It's as though I had not been taken here by force, but came here of my own free will, and that it's not a prison, but my own, ours, ancestral home. . . . How many [came before me]: the Decembrists, members of the Ishutin's circle, Nechaev circle, Narodovoltsi and their offshoots, the children of the present--the last links in the long-living chain."

As I mentioned earlier, Klimova's sentence was commuted. In 1909, she and thirteen fellow female political

prisoners staged a daring escape from their Moscow prison. (Mayakovsky's mother sewed clothing for these women, helping to prepare their escape). Klimova took the Eastern route out of Russia, and traveled the Trans-Siberian railroad to China and then across the world to Paris, where she rejoined some of her comrades. Kan makes a good case showing that later in life she might've grown remorseful and troubled by the people that she and her comrades killed. Nevertheless, the matter of the revolution was pressing. She tried to stay involved in the terrorist organization. At the same time, she married and gave birth to three children. She died in 1918, having lived long enough to see the revolution she worked for go astray when Bolsheviks took over. Her eldest daughter, Natalia Stoliarova, reemigrated to the Soviet Union in 1930s, ended up in the Gulag, and later played a large role as the intermediary between USSR and the West, surreptitiously connecting Soviet artists and writers to the audience in the West. Her story deserves a separate narrative; it undercuts all familiar stereotypes of life in the Soviet Union.

The story of Klimova's life has inspired several "belles lettres" writers. Kan's volume is framed as a response and explication of Varlam Shalamov's documentary tale, "The Gold Medal." (Shalamov is best known for his Gulag narrative, Kolyma Tales.) She appears as a character in Solzhenytsin's August 1914 and Suicide by Mark Aldanov. Kan is meticulous in gathering all the memoirs and documentary sources that mention her name.

One of the most appealing features of Kan's fascinating study is its incredibly thorough work with the sources: every factual statement is cited and, frequently, annotated, leaving the reader with a complex picture of the revolutionary movements of the early 20th C. If I had one criticism for Kan's approach it's that he makes a little too much of her relationships with the men in her life (and male influences), and while he does a great job of mentioning her relationships with notable women of the revolutionary movement and prominent cultural figures (Zinaida Gippius disliked her intensely), the descriptions of the women are almost always cursory. Many factors probably went into this; Klimova herself probably prioritized the men in her life over the women. I would love to know more about Klimova's mother, the first female Russian medic?? Kan's details about her are scant. I wonder how many documentary sources exist, and how much Klimova knew about her mother. Pulling this thread further would add another dimension to the book.

|

| 1903-1906 |

Klimova was born in Ryazan in 1885; her father, a lawyer, was an elected member of the representative council of small landowners (земское собрание)--Russian Empire's narrow concession to the idea of self-government. Her mother, Liubov Vyropaeva, came from the old Russian gentry and in 1870 became one of the first, if not the first, Russian woman to receive a medical degree--in Switzerland. She specialized in gynecology, established a respectable practice in Ryazan. She died in 1894, undergoing an operation for an ectopic pregnancy. A few years after her death, her husband and Natasha's father married Liubov's sister Olga, and so Natasha's aunt became her step-mother.

At first, Natasha tried to follow in her mother's footsteps. In 1903 she arrived to St. Petersburg and entered the women's higher education courses that would prepare her for the entrance exams to the Women's Medical Institute that by then existed in the capital. In 1904, Russia entered the war with Japan that seemed senseless to most young people, radicalizing many and leading to a renewed vigor in protests against the autocratic government--the protests that in 1905 erupted into general worker strikes and a large scale revolutionary movement, brutally broken up by Nicholas II's government and army. In December of that year, workers and students organized an armed protest in Moscow, and Klimova was among those who carried revolvers and ammunition to the barricade lines.

Klimova joined the Socialist Revolutionary party (illegal, as all socialist parties in Russia at that time), advocating for land reforms (transfer of land to the peasants) and self-government via a democratic election process. Her favorite reading at the time was Nietzsche and Tolstoy, a combination fairly typical to the disenfranchised young people of the rapidly industrializing Russia. According to Kan, from Tolstoy Klimova took the disgust with the existing class system, the wealthy "who feed on the poverty, debauchery, and suffering of millions."

Where Tolstoy rejected violence as the means of attaining social order, Nietzsche took over: "Humanity is what one must eclipse. . . . What matters in a human being is that he's a bridge, not the aim: one can only love the passage and the demise in a human being. . . . I love not those who look to the stars for the reasons to perish as victims, but those who actively bring the sacrifice of themselves to the earth, so that one day the earth can be the earth of the new man." [I'm translating this stuff from the Russian, trying to capture the style of the old-fashioned Russian translations of Nietzsche.]

|

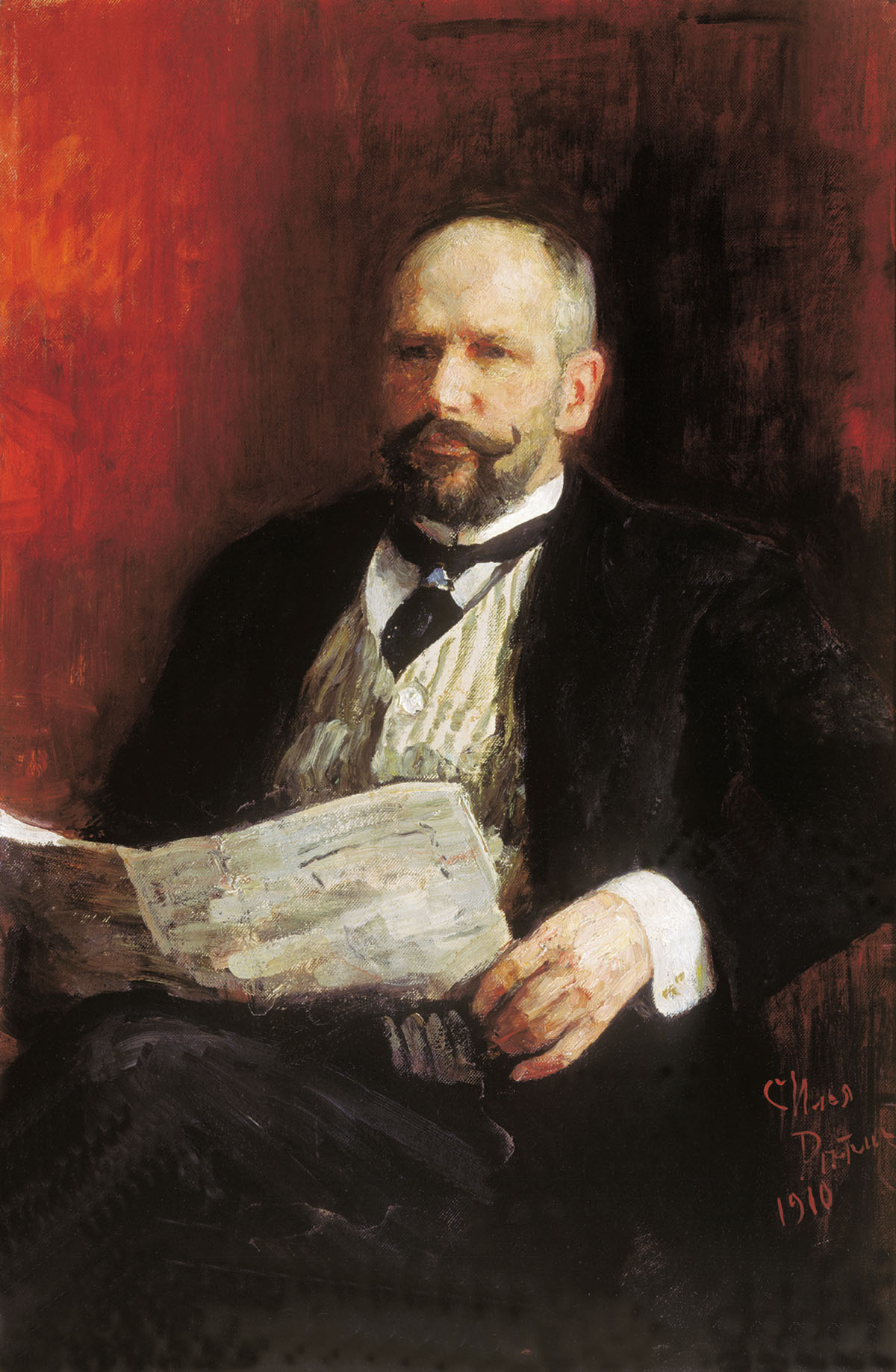

| Stolypin, in Ilya Repin's rendering |

with the hero worship and the challenge to stretch personal and social limits to achieve her goals. In 1906, Klimova joined a terrorist group who aimed to kill

|

| In St. Petersburg prison, 1908 |

In another document, a memoir of being imprisoned in the famed Peter and Paul Fortress, Klimova writes: "I can't shake a very odd sensation. . . . It's as though I had not been taken here by force, but came here of my own free will, and that it's not a prison, but my own, ours, ancestral home. . . . How many [came before me]: the Decembrists, members of the Ishutin's circle, Nechaev circle, Narodovoltsi and their offshoots, the children of the present--the last links in the long-living chain."

As I mentioned earlier, Klimova's sentence was commuted. In 1909, she and thirteen fellow female political

|

| The woman on the left, Tarasova, was a prison guard who facilitated Klimova's (in the middle) and Gelms's (on the right) escape |

|

| Varlam Shalamov |

One of the most appealing features of Kan's fascinating study is its incredibly thorough work with the sources: every factual statement is cited and, frequently, annotated, leaving the reader with a complex picture of the revolutionary movements of the early 20th C. If I had one criticism for Kan's approach it's that he makes a little too much of her relationships with the men in her life (and male influences), and while he does a great job of mentioning her relationships with notable women of the revolutionary movement and prominent cultural figures (Zinaida Gippius disliked her intensely), the descriptions of the women are almost always cursory. Many factors probably went into this; Klimova herself probably prioritized the men in her life over the women. I would love to know more about Klimova's mother, the first female Russian medic?? Kan's details about her are scant. I wonder how many documentary sources exist, and how much Klimova knew about her mother. Pulling this thread further would add another dimension to the book.